You know that classic shot that everyone takes of Angkor Wat? The one with the main temple reflected in the lake with the sun rising in the background? ... well this isn't it. This is what you would see if you turned your back to the sunrise.

I have been fortunate enough to have visited Angkor Wat twice now and I am still in awe. This building is one of the library buildings. It probably didn't house much in the way of manuscripts, but was more likely a place of rest and solitude for the monks.

It is hard to convey the scale of Angkor to anyone who hasn't been there. This building is one of two that are all but lost in the vast outer courtyard of the Angkor Wat complex.

Looking at the photo now, I wonder why I didn't climb up and look inside. I didn't last I was there either.

The lure and promise of the main temple is so seductive that this little temple is quickly left behind.

Angkor Wat itself is just one of the temples of the Angkor region that covers an area of 400 km2. The architecture dates from the 9th to the 15th centuries and is now protected by UNESCO as a world heritage site.

The Library

The Suite Balcony with Ancient bed

OK, so I have to admit, the ONLY reason I booked this hotel was for the "Ancient Bed" ... I mean, how could I resist the description "The Suite Balcony with Ancient Bed" and the opportunity to enjoy "a goblet of cocktail drink" on the balcony after a hard day's touring of Angkor Wat.

I suspect the bed wasn't actually that ancient. Call me a cynic, but I think it had been carved relatively recently. It was tremendously comfortable... and just a little bit romantic don't you think?

A monk's progress

We got pretty excited the first few times we saw monks in Cambodia, with their orange robes they made such wonderful photographic studies. By the time we left Laos, however, we had seen so many we'd ceased to photograph them.

Cambodian Cook-out

We saw this on the corner of a busy street in Phnom Penh... just off Sisowath Quay. It was late afternoon, and there weren't many people around... just lots of traffic... I guess they were expecting a crowd to turn up for dinner.

Happiness is a cyclo ride

We spotted these three little cuties as we were sitting outside a restaurant in Phnom Penh... they spotted us too and waved back.

FREEDOM

ree·dom /ˈfrēdəm/

Noun:

1. The power or right to act, speak, or think as one wants without hindrance or restraint.

2. Absence of subjection to foreign domination or despotic government.

Inside S21 the Khmer Rouge held their fellow citizens captive, while little birds were free to flit on the bars of the cells, a glimmer of life on the outside, but no glimmer of hope.

THE LIVING ROOM

“You’re going to Cambodia?” Maria exclaimed. “You must go visit my friend Simon. He has a restaurant called ‘The Livingroom’... its in Phnom Penh.”

I made a note of the name on my iphone, along with other details... Simon’s partner Sophie. Something to do with the Hotel Combodiana... Maria was babbling away amicably, as she always does.

I told Maria that I had already booked our accommodation and assured her we would seek out ‘The Livingroom’. Maria can be very forceful. She is Filipino, married to an anglo and imports gourmet foods from around the world, and specifically SE Asia. We are customers of hers and have known her for years. Maria is a good saleswoman, open and chatty, and always makes us feel like we are long lost friends. I wonder exactly how much of a friend Simon is... after all, she refers to me as ‘her good friend’ as well.

Months later in Phnom Penh we decide to seek out The Livingroom. It has been recommended by another acquaintance as well, but they, and Maria, were sketchy on the address.

Our Tuktuk driver weaves us through the busy streets and we make our way to Street 222. Unlike New York, the numbered streets in Phnom Penh dont seem to follow any kind of numerical sequence. The street before 222 is 214 and the one after is 228. It doesn’t matter because our driver doesn’t have any more of a clue on how to find the Livingroom than we do.

We travel up and down 222 several times to no avail. I suggest to our driver that he asks someone, but the ability of men to ask for directions seems to have evaded this culture too. Eventually he concedes and asks a fellow Tuktuk driver. After much discussion and waving of hands... mine included, we discover The Livingroom on street 306, about 10 streets further away.

It is an oasis. Shady gardens surrounding an elegant French villa. A soft spoken waiter directs us to a table on the first floor on a wide open balcony. We sink into blue and white cushions on white cane armchairs and study the menu. We are somewhere between lunch and dinner, but have lost all sense of time. Ceiling fans whir gently above us.

I mention Simon’s name to the waiter. It is a tenuous connection and I am half hoping that Simon is not available.

“I am sorry.” He apologies. “Simon is not coming to the restaurant today..”

“Its OK.” I respond. “He is just a friend of a friend.”

We order Soy Chai Lattes and Fish Cakes and spicy Sping Rolls and enjoy the tranquility of our surroundings.

Sometime later the waiter informs me that Simon’s business associate is downstairs. I thank him, but we decide not to make contact. The connection has almost disappeared.

We are loathed to leave the peace and quiet of this lovely villa, but there is still so much we have to see in Phnom Penh... there is a river cruise and dinner. And probably another visit to the FCC for a late cocktail.

Just as we are leaving the garden, I see a young woman sitting at a table. She is slim, attractive and dressed very neatly in black, a laptop and a pile of paperwork spread out across the table. I hesitate.

“Are you Sophie?” I ask.

“Yes.” she says.

“I am a friend of Maria’s, from Sydney. She recommended the Livingroom to us.”

She smiles warmly. And we chat enthusiastically about our travels and Cambodia and Maria. And I am glad. The next time I see Maria, I can tell her I’ve met Sophie.

Faces on the wall

We spill out of the taxi at the Genocide Museum. It is uncomfortably hot.

“How long should we stay here?” we ask our driver. He shrugs. “Its up to you.” he says. He points to a shady spot up the road. “I will wait there for you.” He gestures with his head.

As I approach the ticket office, a man looms in front of me, his face, hideously disfigured... from I can’t imaging what. I turn away, completely confronted. I have never see such deformity. I don’t know what to think. The moment is quickly suppressed from my memory as I focus on what lay ahead.

Inside the gates, the “prison” surrounds three sides of an open courtyard. There is little shade and so we head for the nearest building. This used to be the Chao Ponhea Yat High School, but was converted to a prison during the “reign” of Pol Pot.

The first room I enter is strangely familiar. I have seen photos of it, so the scene comes as no surprise. Images from this prison were featured in the 1992 Ron Fricke film “Baraka”, and it is a place I’ve always wanted to visit. The cheery yellow and white tiled floor was a happy legacy of its schooltime days. The lonely metal bed complete with shackles now a reminder of the horror of its more recent history.

Perhaps because of the confines of the walls, I find this place more disturbing than the killing fields. Perhaps because I find torture so much more disturbing than death. Perhaps because it it is easier to visualise what took place here... or perhaps it is the neverending wall after wall of photos. Photos of real people who were brought here, imprisoned, interrogated and tortured before being carted off in trucks to Cheung Ek to be killed, en masse.

There is one room after another, each one with a bed frame, perhaps a desk, perhaps an instrument of torture. On one wall of each “classroom” is a different photo. Taken by Ho Van Tay, a Vietnamese combat photographer who was the first media person to document Tuol Sleng to the world. The photos are a grisly portrayal of the tortured bodies shackled to the beds.

On the balcony outside, a sparrow flits from wire to wire. Barbed wire that was erected to keep the prisoners in.

We make our way to the second school building. This one was converted into cells. Where the “prisoners” were held captive for months on end.

Beyong the cells, there are rooms and rooms lined with photos. Each prisoner was photographed on arrival. The Khmer Rouge required that the prison staff make a detailed dossier for each prisoner. The original negatives and photographs were separated from the dossiers in the 1979–1980 period and most of the photographs remain anonymous today. Nameless faces. Wall after wall. There is a face of a little girl. She must be about 4 years old. She looks sweet, and of course, innocent of any political crime. The faces stare back. One man appears deranged with terror, the whites of his eyes circling his dark eyes as they nearly pop out of his head. His mouth is a grimace. He must know what fate lies before him. So many people, so many women, so many children. I looked into the eyes of many of the victims to try and see what emotions they may have been experiencing when photographed. Most seem detached and resigned to an unknown fate. A few seem terrified. Not as many as I expected. It beggars belief.

There is a sign on the wall. It is a diagram of a smiling man with red line slashed through it indicating that it is prohibited to smile or make jokes here. I wonder at the need to erect such a sign.

Tuol Sleng Prison

Upon arrival at the prison, prisoners were photographed and required to give detailed autobiographies, beginning with their childhood and ending with their arrest. After that, they were forced to strip to their underwear, and their possessions were confiscated. The prisoners were then taken to their cells. Those taken to the smaller cells were shackled to the walls or the concrete floor. Those who were held in the large mass cells were collectively shackled to long pieces of iron bar. The shackles were fixed to alternating bars; the prisoners slept with their heads in opposite directions. They slept on the floor without mats, mosquito nets, or blankets. They were forbidden to talk to each other.

Most prisoners at S-21 were held there for two to three months. However, several high-ranking Khmer Rouge cadres were held longer. Within two or three days after they were brought to S-21, all prisoners were taken for interrogation. The torture system at Tuol Sleng was designed to make prisoners confess to whatever crimes they were charged with by their captors.

When prisoners were first brought to Tuol Sleng, they were made aware of ten rules that they were to follow during their incarceration. What follows is what is posted today at the Tuol Sleng Museum; the imperfect grammar is a result of faulty translation from the original Khmer:

1. You must answer accordingly to my question. Don’t turn them away.

2. Don’t try to hide the facts by making pretexts this and that, you are strictly prohibited to contest me.

3. Don’t be a fool for you are a chap who dare to thwart the revolution.

4. You must immediately answer my questions without wasting time to reflect.

5. Don’t tell me either about your immoralities or the essence of the revolution.

6. While getting lashes or electrification you must not cry at all.

7. Do nothing, sit still and wait for my orders. If there is no order, keep quiet. When I ask you to do something, you must do it right away without protesting.

8. Don’t make pretext about Kampuchea Krom in order to hide your secret or traitor.

9. If you don’t follow all the above rules, you shall get many lashes of electric wire.

10. If you disobey any point of my regulations you shall get either ten lashes or five shocks of electric discharge.

Wikipedia

On the road to Sieam Reap

I shot this out of the car window somewhere between Phnom Penh and Siem Reap in Cambodia. Not really typical of the landscape, but interesting none the less.

A dark place

Formerly the Chao Ponhea Yat High School, named after a Royal ancestor of King Norodom Sihanouk, the five buildings of the complex were converted in August 1975, four months after the Khmer Rouge won the civil war, into a prison and interrogation center. The Khmer Rouge renamed the complex "Security Prison 21" (S-21) and construction began to adapt the prison to the inmates: the buildings were enclosed in electrified barbed wire, the classrooms converted into tiny prison and torture chambers, and all windows were covered with iron bars and barbed wire to prevent escapes.

From 1975 to 1979, an estimated 17,000 people were imprisoned at Tuol Sleng (some estimates suggest a number as high as 20,000, although the real number is unknown). At any one time, the prison held between 1,000–1,500 prisoners. They were repeatedly tortured and coerced into naming family members and close associates, who were in turn arrested, tortured and killed. In the early months of S-21's existence, most of the victims were from the previous Lon Nol regime and included soldiers, government officials, as well as academics, doctors, teachers, students, factory workers, monks, engineers, etc. Later, the party leadership's paranoia turned on its own ranks and purges throughout the country saw thousands of party activists and their families brought to Tuol Sleng and murdered. Those arrested included some of the highest ranking communist politicians such as Khoy Thoun, Vorn Vet and Hu Nim. Although the official reason for their arrest was "espionage", these men may have been viewed by Khmer Rouge leader Pol Pot as potential leaders of a coup against him. Prisoners' families were often brought en masse to be interrogated and later murdered at the Choeung Ek extermination center.

In 1979, the prison was uncovered by the invading Vietnamese army. In 1980, the prison was reopened by the government of the People's Republic of Kampuchea as a historical museum memorializing the actions of the Khmer Rouge regime.

Wikipedia

Skulls

Skulls on display at Choeung Ek Stupa at the killling fields outside Phnom Penh. On some of the skulls you can see the marks where the victims were bludgeoned to death... to avoid wasting bullets.

Choeung Ek Stupa

The Stupa at Choeung Ek (the killing fields) houses some of the bones of the 9,000 people who were killed at this site. Built as a memorial to the thousands of people who died here. There are over 5,000 skulls on display, arranged according to age and sex.

Life on the River

We sit outside a cafe on Sisowath Quay in Phnom Penh, while we wait for our boat cruise on the Mekong. We drink half price Margaritas and marvel at how cheap they are compared to home.

We think about sunset over the Mekong and all the romance that image conjours up.

We join our fellow tourists on the top deck of the ferry. The boat slides out into the Tonle Sap River and we quickly flow into the confluence with the Mekong River.

It is pleasant on the river, several degrees cooler than in town. And the sun is setting. Our boat trip takes us across the width of the Mekong, towards the opposite shore, where the land is only just visible from the heart of Phnom Penh on the western bank. “How good is this!” we say to ourselves, smugly, the gentle breeze cooling our skin. The air is clean and clear, away from the all pervasive wood-fire smoke that lingers over the city.

On the other side of the Mekong, the shantys, the houseboats and the poor slowly come into focus as we approach the bank. On these houseboats, I see a naked child playing, and a girl in green pyjamas sits, her legs dangling overboard, while she eats a bowl of food. Nearby there is a mother, squatting as she prepares a meal, her children crowded around her.

On shore, where the ramshackle houses tilt precariously towards one another on spindly bamboo legs, children play in the dirt. Skinny chickens scurry around and the doleful dogs languidly roam the banks. The whole shoreline, a canvas of poverty and community, is bathed in the warm light of the setting sun. I think about the story of the Three Little Pigs, one puff and the house of sticks would come tumbling down. Silly, how childhood stories can be so poignant.

Directly behind me, the view to the west is magnificent, the golden orb of the sun is sinking heavily into the feathery soft clouds of the sunset. The ornate roofs of the temples are silhouetted against the glowing sky.

Here on the East bank, however, no-one notices its splendor ....except perhaps, the girl in the green pyjamas.

Chicken Amok

I had a head cold when I was in Cambodia, so this quickly became one of my favourite dishes... it was so tasty. Chicken Coconut Curry... Oh and fresh coconut juice.

Can't talk now... I'm in a meeting

A young monk takes a mobile phone call during a religious ceremony at Choeung Ek Memorial in Phnom Penh.

ROMDENG... "Its more than just Spiders."

“Can we see the spiders?” We asked.

“Yes.” He replied gently and led us through the French Colonial villa. Through the leafy courtyard, across the wide verandahs, under high ceilings and out to the bustling kitchen.

On the edge of the servery, through the translucent sides of a large tupperware container, we saw a cluster of slow moving legs. Tarantulas. He scooped one out, tenderly and placed it with great care on the stainless steel bench.

“You can touch it.” He urged. “It cannot hurt you.”

We looked at the specimen and laughed, nervously.

“Its OK.” I said. We’ll just take some photos instead.

“It is safe. See.” And he picked it up and let it walk up his arm to demonstrate how docile it was, before placing it on a large dinner plate for our viewing pleasure. I backed away a little.

He smiled. “It is safe, it can’t hurt you.” He said again. He was tall for a Cambodian, young with a gentle smile and a gentle nature. His English was good and his diction clear.

I took a deep breath and bravely reached out and touched its soft abdomen with my index finger. Just so I could say I’d done it.

“We will come back here tonight for dinner.” We said. But we wont be eating the spiders.

He laughed and took us out past the kitchen to the swimming pool.

“When you come back, you can swim.” He said helpfully. The pool looked very inviting.

“Do you eat the spiders?” I asked.

“Yes. Of course.” He replied.

Romdeng (meaning galangal in Khmer) is a training restaurant, run by former street youth, even the furnishings and paintings on the walls have been made by students.

We returned for dinner that night. Choosing a table in the courtyard. We ate Banana Blossom Salad, Pork with Chili and Ginger, and Chicken Amok (a Khmer coconut curry.) We drank watermelon juice with chili, minted lime juice with galangal and ubiquitous Pina Coladas.

The man at the next table ordered spiders. Described on the menu as ‘Crispy Tarantulas with Lime and Kampot Black Pepper Dip.’ At $4.00 for three spiders, it is a very affordable dish. The spiders are dipped in flour and thrown into the oil, live. A dreadful demise, even for an arachnid. We watched as the man took his first tentative bite. “Tastes like spider.” He announced. (I’ve been told they taste a bit like chicken.) I could contemplate nibbling on a crispy leg, but the thought of the gooey abdomen. Eek.

Although it is now considered a delicacy, it is thought that the Cambodians’ penchant for spiders may have started out of desperation during the years of Khmer Rouge rule, when food was in short supply.

We returned to the serious business of dessert. Coconut ice cream, served in a martini glass with piccolo wafers. As they say at Romdeng... “Its more than just spiders!”

Our tuktuk driver was waiting patiently for us in the dark street outside. We feel “Colonial guilt.” We dined, while he waited. But competition is fierce for a tuktuk driver in this town, and it is worth his while to wait for us.

“To the FCC.” We tell him. For the night is still young and we are in Phnom Penh.

The Killing Fields

I don’t normally take audio tours when I visit places. I like to do my own research and visit at my own pace. I’m not really one for rules or too much structure. But upon entering the Choeung Ek site... the Killing Fields, I was automatically handed a headset and audio player, and so it was a done deal. The narrative began with eloquent words to an underscore of peaceful classical music.

It was warm and sunny and at first it was difficult to comprehend what at had taken place here. But the audio tour drew us in and led us gently along peaceful paths to places that had such a violent and hideous history. The serenity of the location made it almost impossible to accept that these atrocities had actually taken place here, despite the clear evidence of clothing and bone fragments and obvious burial mounds.

I wanted to be here, as it was a far cry from sipping cocktails on the third floor balcony of the Foreign Correspondents Club, where we spent the previous evening. This is where history actually took place. This would become a backdrop and frame of reference for the remainder of our visit to Cambodia... and this was confronting.

Choeng Ek is the site of a former orchard and Chinese graveyard about 17km south of Phnom Penh. Between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge executed about 17,000 people at the Killing Fields. Under Pol Pot’s “leadership” Cambodians killed Cambodians. Here at Choeng Ek, nearly 9,000 bodies were discovered in mass graves. Human bones and remnants of clothing still litter the site.

As a policy, bullets were not to be wasted, so the people were beaten to death, poisoned or buried alive, often having dug their own mass burial pits.

We walk around the site, detached, seeking refuge from the heat under the cool shade of the trees. By listening to the headsets, we each make our own solitary journey, no-one talks, everyone listens. I observe other tourists, headsets in place, sitting under a tree, lost in thought and faces sombre, we all reflect on what we are hearing.

I was 18 when these atrocities took place. Attending art school, meeting boys, gaining an education and attending parties. I had no idea.

...and the rest of the world stood still.

Life in the Shadows

The Skeleton of the new Sokha Hotel rises over the Mekong River. In its shadow huddles a ramshackle hovel... someone's home. Across the river a shanty town clings to the shoreline.

The Sokha Hotel (Chrouy Changva) will reside on a 14 hectare Riverfront project and will include a 798 rooms and suite, an international convention centre, Jasmine Spa, high end condominiums, exclusive villas, entertainment centers, shopping centers, restaurants and residence club house. It will also include: talian Restaurant, Japanese Restaurant, Chinese Restaurant, Bar & Karaoke, Irish Pub, Sports Bar & Musical Club, Beer Garden, Business Centre, Library, Sky & Cigar Lounges and Landscaped Swimming Pool.

I wonder if the shanty town will survive for much longer. If the developers don’t demolish it. I am sure the next time the Mekong floods it will carry it away in its path.

Sultana Cake.. with extra sultanas.

...hang on a minute... some of those sultanas are moving.

I spotted these in the markets in Phnom Penh... looks like the flies spotted them first. :)

Alison in the depths of Phsar Kandal

Phsar Kandal or Kandal market is a sprawling, low-slung market full of fresh produce. Locals meet here at the noodle bars or come here to buy meat, fish, fruit and vegetables. The character of the market is very Vietnamese as there is a large population of Vietnamese people in this area of Phnom Penh. Despite being only one block away from the riverfront, few tourists venture into its dark interior, which makes it all the more sweet for those of us who do! The markets also house tailors, jewellers and electronics stores as well as fortune tellers and beauty parlours... something for everyone!

Phnom Penh Markets

We leave the hotel, and make our way past the tuk tuk drivers and sunglass salesmen. Sisowath Quay is always teaming with life... and traffic. We are looking for something to do, something different, something to photograph. At the next intersection we turn left again and practically fall into a local street market. Away from the bustle of the main street we find ourselves in another world.

Our pace quickens as we sense the photographic opportunities ahead of us. We follow our eyes, our ears and our noses into the thick of the produce markets where the air is buzzing with energy.

We take one more turn to the left and plunge into the heart of the market, where it is dark and under cover. SpiraLling inward, into the dark depths within. Dried fish hang in garlands around the stalls, fresh vegetables tower up on tables and chunks of indeterminable meat hang on hooks from above. Beams of light, filtering through the broken canopy, beckons us further inward. Here, in steamy kitchens, enormous pots of soup are simmering. Women work in dim light at sewing machines, and children play in the wet concrete alleyways.

Everywhere we turn we are presented with a cameo of Cambodian life. We are exhilarated by the images we are capturing, images that will stay with us forever.

The Royal Palace

The Kings of Cambodia have occupied the Royal Palace since it was built in the 1860s, except for a period of absence when the reign of the Khmer Rouge plunged the country into turmoil.

Two Dollar

Behind the Killing Fields a little boy stretches out his hand. His arm is so skinny it fits comfortably through the mesh of the chain-link fence of the memorial park. He holds up two fingers and pleads with his eyes. “Two dollar?” He says.

Around us are the mass graves where thousands of people were buried after they were brutally killed by the Khmer Rouge in the late ‘70s. There is a breeze blowing across the rice fields, shimmering in the warm sunshine. Here, under a canopy of trees, it is cooler. I watch a butterfly land on the fence and move on. The air smells of flowers. I have been listening to a piece of classical music playing on the headset provided at the entrance to this site and reflecting on the genocide that took place in this now peaceful landscape.

“Two dollar?” He cries out again, and again, insistently.. He follows me along the fence. Clinging to the mesh as he goes.

I could give him two dollars. I could give him two hundred dollars, just as easily. I actually have a $2 coin in my wallet. I look across to Stan, he is suffering the same internal agony that I am. Nothing compared to the agony of a starving child. Nothing compare the horrors that have taken place on this soil.

“No.” I say to the boy. “No, I am sorry. No” And I move away.

I am sorry. Deeply sorry.

To give money encourages begging. I have taken the moral high ground. But a child doesn’t understand that. I support international charities that help third world countries. I give money where I believe it goes towards the greater good. But my conscience will continue to be troubled by moments like this. It is the first day of our trip, and I am unprepared. I make a mental note to carry some fruit with me next time. At least then, I will have something to give.

As we leave the Killing Fields a young girl asks me for money. “No.” I say again.

“Water?” She asks, hopefully.

We are already in the car. Through the window we hand her our half-empty bottle of water as we drive off.

It is the the little boy’s words that remain with me... “Two dollar?” I will spend less than two dollars on my next mango juice or half-priced cocktail. Two dollars wouldn’t even buy a cup of coffee back home.

When my children were little, the toothfairy brought them two dollars for each tooth they lost.

Phnom Penh

Its Christmas Eve... I think.

Our room is pitch black. I close my eyes and open them again to reassure myself that there is absolutely no ambient light whatsoever. Open, close, open, close. Nope, no difference at all.

I reach out and locate my mobile phone and use it as a torch to navigate the room, grabbing my sarong on the way. Our suite is about 40ft long, with a single corridor running down its length from front door to balcony... The bedroom has no windows and the lounge area, adjacent to the balcony is heavily shuttered, keeping out the light, the heat and the noise of Phnom Penh.

The shuttered doors shudder open, and I slip out onto the balcony. The sun will rise soon, the eastern sky is already tingeing pink and soft vespers of breeze will soon give way to intense heat.

I lean over the balcony to survey the street below, careful not to catch myself on the thorns of the bougainvillea festooning the French Colonial ironwork. Below me the curbside has not yet filled with taxis and tuktuks. But across the road, the quay is already full of people walking and exercising. A man bounces a ball as he walks, I can hear the tump, tump, tump of the ball hitting the pavement.

Further up the quay I can see a disparate collection of women and men who are line-dancing. Their singsong music competing with another group of younger people, line-dancing to Asian techno pop. The cars and bikes honking their horns adds another line to the musical score that forms the soundtrack of Phnom Penh. And I think I can detect a Muslim call to prayer adding yet another layer. Odd, as I thought of Cambodia as being primarily a Buddhist country with a little Hinduism and Roman Catholicism left over from the French.

The hotel overlooks the Tonle Sap River, just as it leans in to embrace the mighty Mekong River. On the long peninsular between the rivers a massive hotel is under construction, its skeleton rising up out of the landscape like a predatory beast. Beyond that, on the far shore of the Mekong a miserable shantytown of timber houses clings to the muddy banks, where the poor of Phnom Penh eke out an existence under the shadow of progress.

In the street below our driver Mr Ram, dressed in a crisply ironed pink shirt is obsessively polishing his already very shiny brown sedan. The car door is open and his radio is adding to the growing cacophony. Ravi the tuktuk driver has pulled up, and is in a huddle of conversation with some other tuktuk drivers. When I go downstairs for breakfast they will assail me with their calls. “tuktuk Madame... where you go... you want a tuktuk Madame?”

Madame, madame, madame.

CAFE AUBERGINE (your home away from home)

“You know...” She said plainly. “We have a whole other life back at home... And its not this.”

It was their last night in Hanoi and they were perched on the first floor balcony of Cafe Aubergine. She had just taken a photo of the street below. There was something about the light that reminded her of a film set. That, and the relative stillness of the scene. Only hours before it had been near impossible to cross the narrow street as motorbikes, cars, cyclos, tourists and hawkers poured through the streets like in slow moving and impenetrable torrent.

“Its like someone has pressed the “pause” button on our life at home. This... this is our reality now, but when we get home, this will just be a memory. It will cease to exist. We will just resume our lives, like this never happened.“

He was listening, but he said nothing, waiting for her to continue. He sipped on his beer and looked out at the street.

A swirl of images filled her head. They had seen so much in the last three weeks. Each day, new sights had overlaid the ones from the day before and it was hard to remember any of it. The images continued to swirl, but she couldn’t hold on to a single one. It was like catching butterflies.

“... this will continue after we leave. Its like a parallel universe. Its like time travel. We will press the pause button here when we leave. And it will stay like that, for us, until we return. If we ever do...” She trailed off... lost in thought.

It was her third visit to Hanoi, and the old French quarter had wrapped itself around her with the warm familiarity of an old sweater. It was like watching a favourite movie for the third time. She was no longer afraid of missing something and could lay back and drink in the detail. The reality of Hanoi was palpable. The heady smell of wood fire smoke, the sweet taste of organically grown vegetables. The relentless honking of horns. The press of people negotiating the horrendously overcrowded footpaths. And the shimmering tableaux of sights. It was impossible to imagine being anywhere else.

“Could you live here?” She asked. “I mean, if we had an income and we lived in a French Colonial villa. Do you think could you live here?”

He paused, ever so slightly before he answered.

“No.” He said. “I don’t think so.”

“No.” She agreed. “I couldn’t either.” But she continued to mull over the idea in her mind as she stared out into Hanoi’s cool night air.

The glass wall of the balcony was just lower than the height of the table. A clumsy wave of her hand and she could easily knock her glass and send it skittering through the air and crashing onto motorbikes or people on the pavement below.

She ordered another Mango Lassi... realising it would be her last one. She wasn’t sad to be returning home, but she wasn’t happy about leaving Hanoi either. Limbo.

It was different this time. They were returning to a life together. So she didn’t feel the wrenching heartache of leaving that usually gripped her. But there was a sense of melancholy, never-the-less. And it was a feeling she knew he didn’t share.

She sighed and looked across the table at him. “This is probably the last time I will ever be in Hanoi.” She said finally, her voice catching in her throat. She was fighting a deep sense of loss that was welling up inside her. She felt a sense of mourning, but there were just too many other places in the world she still wanted to see.

“No.” He said, and he smiled at her. “I think we will come back.”

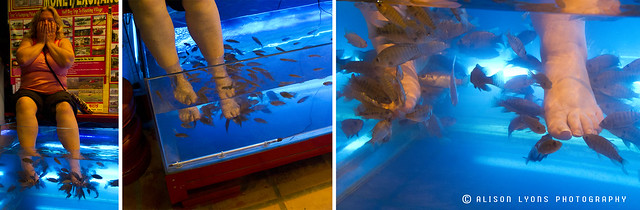

FOOT SPA

Foot Spa - Siem Reap

So these are my feet... or at least one of them, in a fish tank in Cambodia... After a long day clambering over the temples of Angkor Wat, I decided to try the fish foot massage in Siem Reap. The fish eat the dead skin off your feet. Yeah I know, it sounds icky and its like death by tickling.... but after 5 minutes of uncontrollable laughter (mine that is) it feels amazingly good... and I couldn’t begin to describe how smooth and soft my feet were afterwards.

It costs $3 for half an hour... or as long as you can stand it. The tanks have been set up outside travel agents and shops in Siem Reap in an effort to attract customers.

We arrived home in Sydney this morning after three weeks in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, only had two hours sleep, so stayed tuned, I will be posting a lot of images, once I’ve caught up on some sleep.